One of my favorite Dolly Parton songs is “Just Because I’m A Woman.” To love Dolly is to know that her whole deal is a deep understanding of femininity as first and foremost performance art—it’s there in “False Eyelashes” and in “The Bargain Store” and in the macabre, bleak story songs like “Down from Dover” and “Robert”—but “Just Because I’m A Woman” is the apex of this argument.

“I can see you're disappointed,” she begins, “By the way you look at me/ And I'm sorry that I'm not/ The woman you thought I'd be/Yes, I've made my mistakes/ But listen and understand/ My mistakes are no worse than yours/Just because I'm a woman”

The type of womanhood Dolly is describing is the kind I always operated from when thinking about feminism. It understands that the limitations of womanhood are structural, not biological, not bound in any sort of essential nature, and that womanhood is not any more exalted or morally righteous or smarter or kinder or empathetic or better smelling than any other gender. The barriers and detriments around it come from expectations—from societies, social groups, other people, oneself—and are not an inherent part of being a woman. In Dolly’s song, being a woman means freely makes mistakes, sleeping around, actually wants to have sex and claiming the right to talk about all of it even if the wider world does not want to listen.

But there is a whole strain of feminism that understands womanhood primarily as a wound—that the most authentic experience of womanhood is injury, and a very specific type of pain. Every day, I read with horror about the ascendancy of TERFs (trans exclusionary radical feminists) in British media, university spaces and political power. I see the language of exceptional, essentialist womanhood used interchangeably with vaguely feminist arguments.

In this version of feminism, womanhood is a prize to be held up and valuable because of who it excludes. It’s wound as outerwear—womanhood is akin to a grievance, but a grievance only certain kinds of women are allowed to express directly. And it’s believed that the grievances of upper class womanhood stand in for the grievances of all womanhood. So that a symbolic, but ultimately immaterial question like whether or not to take your husband’s last name becomes philosophically linked to women experiencing female genital mutilation . A woman being spoken over in a meeting somehow becomes the great feminist cause to devote endless thinking to, instead of the women being forced to work long hours on a factory floor. When “woman” means “wound”, there is no scale of pain—it’s all the same, isn’t it? That woman’s pain over there, that could be alleviated by systemic changes, is actually better served as symbolism for the women on top—curlicues for arguments to get what the woman on top wishes, instead of actual change for everyone.

I think I knew something was up with a certain type of white woman fiction writer feminist when I came across a later Fay Weldon novel that argued that the real threat to feminism in the UK was...eastern European immigrant women who were just too sexy to hire as housekeepers

There's a direct line from that type of feminism which is really "the world should be as easy to me as the white man beside me, everyone else be damned" to this current crop of women who claim to think deeply about womanhood, who have somehow never understood it has always been conditional

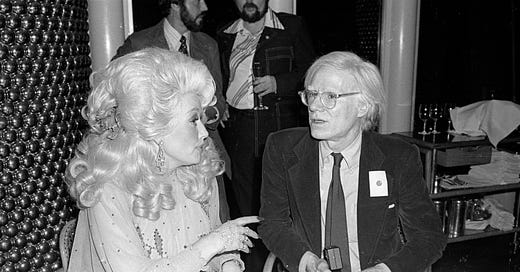

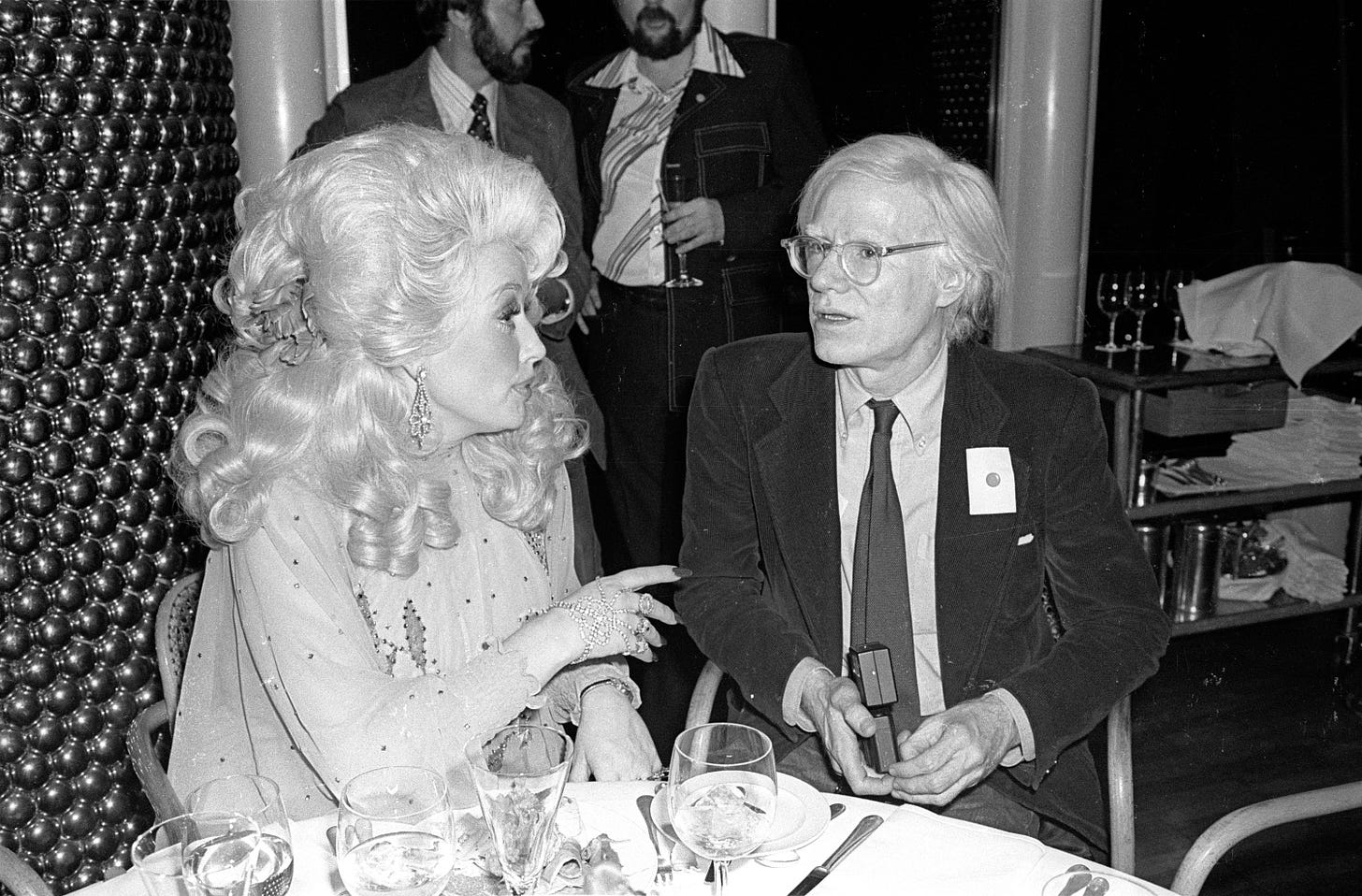

I’ve been thinking about all of this, trying to write about all of this, for months, prompted in part by reading Breanna Fahs’ Valerie Solanas biography from a few years back. Solanas is most famous for shooting Andy Warhol, but she also, of course, wrote her S.C.U.M. manifesto—S.C.U.M. standing for the Society for Cutting Up Men.

The whole biography reads as an alternative history to the 1950s—before joining the New York underground, Solanas grew up in a fractured family in the 1950s, becoming pregnant twice as a teenager, her children taken from her so that she could maintain the fiction of virginity and finish school. In the late 50s, she was both one of the few women grad students in her psychology program and a sex worker—she had no family financial support and eventually had to drop out of school. She was homeless for most of her adult life, profoundly antisocial before she latched on to Warhol as a symbol of everything she was fighting against. Her gender and sexuality were illegible to most around her—she dated men and women, mostly had long term relationships with men, sometimes identified as a lesbian but also often spoke of being asexual. Notably, when she first tried to infiltrate Warhol’s circle because she hoped he would help her produce her work, most of the supposed bohemians in it rejected her because she “dressed like a dyke” and were sometimes actually frightened of her in part because of her gender “confusion”—her rejection of outward femininity while also reviling men. I find it so provocative that on the day Solanas shot Warhol, she put on her best dress and make up.

At times, the biography reads like a dark comedy of manners of what used to be called the underground. After Solanas shoots Warhol, she’s adopted by radical feminists (in the old sense of the term) involved in the more mainstream National Organization of Women. Betty Friedan hated Solanas, told NOW members they couldn’t provide her legal support because she advocated violence. But, as one of Solanas’ supporters points out, Friedan gave this edict a few weeks after she herself chased her husband out their Hamptons beach house with a butcher knife. In that, I see a germ of what’s flowered today—the respectable, branded versions of feminism denying other women’s realities, even as they themselves experience them.

Solanas herself had no use for organized feminists. She saw the women involved in NOW as glorified Daddy’s Girls—performing goodness and balance in order to get special favors from those in charge. Of her hopes for SCUM, she wrote “SCUM will become members of the unwork force, the fuck-up force; they will get jobs of various kinds and unwork.”

Solanas was a visionary—in the early 1960s, her writings predicted the rise of IVF; gay marriage; an evolution of the gender binary and an understanding of the consolidation of information into corporate ownership. Her writings also at times read incredibly dated. The constant split of the world between only men and women is a logic and binary that, like Friedan with her butcher knife, worried about feminists being represented as violent, ignores the complexity of her own life.

I needed something to balance all this—something between the binary thinking inherent in gender anarchists like Solanas and the TERF gatekeepers of womanhood and first and second wave feminists—all unable to imagine bigger numbers than 2. So I have also been reading Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí’s The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses. There, Oyěwùmí writes

I came to realize that the fundamental category “woman”—which is foundational in Western gender discourse—simply did not exist in Yorubaland, prior to sustained contact with the West. There is no such preexisting group characterized by shared interests, desires, or social position. The cultural logic of Western social categories is based on an ideology of biological determinism: thee conception that biology provides the rationale for thee organization of the social world. [In the West] social categories like “woman” are based on body-type and are elaborated in relation to and in opposition to another category: man; the presence or absence of certain organs determines social position…[But] prior to the infusion of Western notions into Yoruba culture, the body was not the basis of social roles, inclusions, or exclusions; it was not the foundation of social thought and identity. Most academic studies on the Yoruba have, however, assumed that “body-reasoning” was present in the Yoruba indigenous culture. They have assumed the Western construction as universal, which has led to the uncritical usage of these body-based categories for interpreting Yourba society historically and in the contemporary period.

It is especially telling, I think, that some women who write fiction cannot imagine outside of what Oyěwùmí calls the “bio-logic.” It’s actually a little depressing. But it helps to remember all the cultures and people and singers and writers who can.

I love your concept of white, wound-based feminism flattening the "scale of pain." How can we build feminism that makes space for all kinds of pain, without equating them? Or should we even try? If the answer is to listen to more Dolly Parton, I'm very, very here for it...

So good!! Especially insightful to point out the problem of identity as wound, and how that gets externalized: “Only I know my pain, therefore your pain is acceptable only if it reflects or mirrors mine.” This construct feels deeply accurate in the context of the feminist movement, past and present. It also had a tinge of existential panic…if we can’t make the wound a weapon or armor, then our existence, our very matter, is at risk of annihilation. Of course unbeknownst to women in this camp is that they are actually participating in that annihilation through their wound as identity trope… so thoughtful this piece! Thank you for writing it 💖